Jornada Mogollon

Approximately 2,000 years ago the Jornada Mogollon people were living in the El Paso area. They were essentially Neolithic stone age people who were living off the land. The climate was a little wetter back then, but it was still a very difficult existence.jpg) .

.

In several different locations in and around El Paso one can find Indian rock art, both the stone carvings called petroglyphs and the ancient paintings which are called pictographs. One also can find stationary mortars, which were used to grind seeds such as mesquite into flour. I hav.jpg) e also seen shards of the coarse pottery they made (which today we call El Paso Brown) in several different locations, including in the desert about a mile northeast of Walter Clarke Park in far east El Paso.

e also seen shards of the coarse pottery they made (which today we call El Paso Brown) in several different locations, including in the desert about a mile northeast of Walter Clarke Park in far east El Paso.

Since these native people did not know how to make metal, their pottery shards are often the most conspicuous record of them. Archaeologists have many different useful subdivisions of prehistoric pottery based upon chronology, the regional groups making the pottery, as well as the shapes and decoration.

El Paso Brown pottery is primitive and very easily broken when compared with the pottery which was being made at the same time by the Chinese, the Greeks and Romans. El Paso Brown pottery remained essentially unchanged for 1,000 years.

The red, fine, shiny Roman pottery called terra sigillata (Samian ware in the UK) is a much.jpg) more advanced pottery which was being made at about the same time. The Romans knew about bronze and iron, concrete, and were building enormous domes like the Pantheon at about this same time.

more advanced pottery which was being made at about the same time. The Romans knew about bronze and iron, concrete, and were building enormous domes like the Pantheon at about this same time.

The porosity of the local native American pottery is quite high. The pot shards seen in El Paso are typically dull colors of brown to pink, and very often the cores of the shards are dark or black. This indicates a low temperature firing, where the pots are not.jpg) isolated from the fire.

isolated from the fire.

The clay used to make this pottery contained abundant carbon derived from plant matter. The percentage of large, coarse inclusions in the clay is high. These large pieces (called temper) are essential. The finished pottery averages 5.7 mm thick with a standard deviation of 0.889 mm.

-

Kilns were not used to fire this Native American pottery, rather the pots were typically air dried for a few days or weeks, then fired quickly in a bonfire or pit. The temperature of this firing method rises very rapidly, and then it also declines quickly. Even after air drying these pots contained as much as 10% moisture or more in the clay. In a bonfire.jpg) the temperature rises past 212 degrees F (100 C) rapidly, and the water remaining in the dried clay boils off with explosive force. To keep the pot from shattering during firing, coarse pieces in the clay are essential to provide pathways for this steam to escape.

the temperature rises past 212 degrees F (100 C) rapidly, and the water remaining in the dried clay boils off with explosive force. To keep the pot from shattering during firing, coarse pieces in the clay are essential to provide pathways for this steam to escape.

When clay which contains large amounts of carbon from plant matter is first heated, the organic material in the clay chars and turns bla.jpg) ck. Over time the surface of the pot lightens in color from black to red or brown, but the core will frequently remain black due to short duration firing. This depends upon the length of time the pot is fired, and also how sandy or fine the clay is.

ck. Over time the surface of the pot lightens in color from black to red or brown, but the core will frequently remain black due to short duration firing. This depends upon the length of time the pot is fired, and also how sandy or fine the clay is.

Some El Paso Brown shards have been fired sufficiently to burn out the carbon core entirely, but most contain black cores.

The El Paso Brown pottery was fired at a very low temperature of 1,100 to 1,500 degrees F (600 to 800 degrees C), and this firing may have taken less than one hour. These pots would hold water for a little while, but were fairly porous to liquids if stored for long periods.

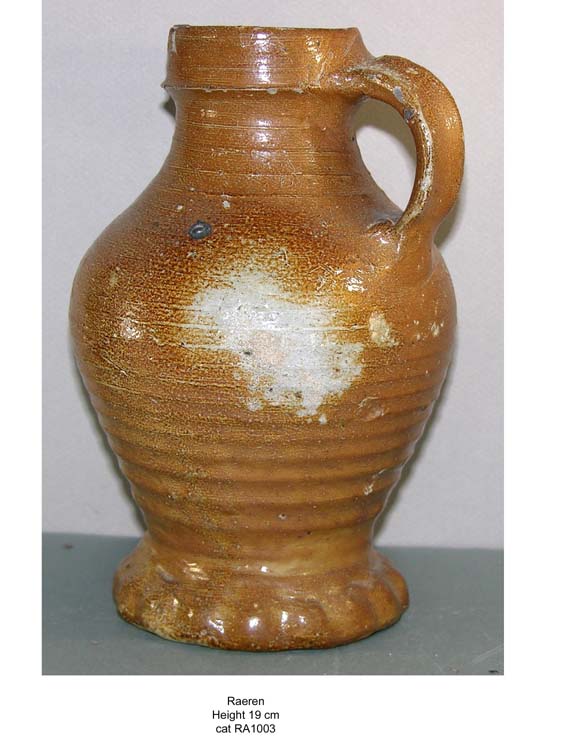

Compare this to stoneware which was fired in kilns in Europe from the early 1400s to the 1600s. This pottery was fully fused and was virtually impervious to liquids. The firing of this stoneware typically t.jpg) ook several days and then an equal amount of time or more to cool down before the potter could safely empty the kiln. The temperature needed to vitrify this clay into a very low porosity and re

ook several days and then an equal amount of time or more to cool down before the potter could safely empty the kiln. The temperature needed to vitrify this clay into a very low porosity and re.jpg) lative high strength true stoneware was 2,400 to 2,500 degrees F (1,300 - 1,400 degrees C). Note that this is a really high temperature; a little beyond cone 10 for people who use kilns.

lative high strength true stoneware was 2,400 to 2,500 degrees F (1,300 - 1,400 degrees C). Note that this is a really high temperature; a little beyond cone 10 for people who use kilns.

While the pottery made by the Jornada Mogollon people may have been somewhat primitive when compared with the Romans or Greeks, I am certain that virtually all El Pasoans living today would not survive more than a few days at most if they were stranded out in the Chihuahuan desert surrounding El Paso.

-

The native peoples were very intelligent and hardy indeed.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

.jpg) .

. In several different locations in and around El Paso one can find Indian rock art, both the stone carvings called petroglyphs and the ancient paintings which are called pictographs. One also can find stationary mortars, which were used to grind seeds such as mesquite into flour. I hav

.jpg) e also seen shards of the coarse pottery they made (which today we call El Paso Brown) in several different locations, including in the desert about a mile northeast of Walter Clarke Park in far east El Paso.

e also seen shards of the coarse pottery they made (which today we call El Paso Brown) in several different locations, including in the desert about a mile northeast of Walter Clarke Park in far east El Paso.Since these native people did not know how to make metal, their pottery shards are often the most conspicuous record of them. Archaeologists have many different useful subdivisions of prehistoric pottery based upon chronology, the regional groups making the pottery, as well as the shapes and decoration.

El Paso Brown pottery is primitive and very easily broken when compared with the pottery which was being made at the same time by the Chinese, the Greeks and Romans. El Paso Brown pottery remained essentially unchanged for 1,000 years.

The red, fine, shiny Roman pottery called terra sigillata (Samian ware in the UK) is a much

.jpg) more advanced pottery which was being made at about the same time. The Romans knew about bronze and iron, concrete, and were building enormous domes like the Pantheon at about this same time.

more advanced pottery which was being made at about the same time. The Romans knew about bronze and iron, concrete, and were building enormous domes like the Pantheon at about this same time.The porosity of the local native American pottery is quite high. The pot shards seen in El Paso are typically dull colors of brown to pink, and very often the cores of the shards are dark or black. This indicates a low temperature firing, where the pots are not

.jpg) isolated from the fire.

isolated from the fire.The clay used to make this pottery contained abundant carbon derived from plant matter. The percentage of large, coarse inclusions in the clay is high. These large pieces (called temper) are essential. The finished pottery averages 5.7 mm thick with a standard deviation of 0.889 mm.

-

Kilns were not used to fire this Native American pottery, rather the pots were typically air dried for a few days or weeks, then fired quickly in a bonfire or pit. The temperature of this firing method rises very rapidly, and then it also declines quickly. Even after air drying these pots contained as much as 10% moisture or more in the clay. In a bonfire

.jpg) the temperature rises past 212 degrees F (100 C) rapidly, and the water remaining in the dried clay boils off with explosive force. To keep the pot from shattering during firing, coarse pieces in the clay are essential to provide pathways for this steam to escape.

the temperature rises past 212 degrees F (100 C) rapidly, and the water remaining in the dried clay boils off with explosive force. To keep the pot from shattering during firing, coarse pieces in the clay are essential to provide pathways for this steam to escape.When clay which contains large amounts of carbon from plant matter is first heated, the organic material in the clay chars and turns bla

.jpg) ck. Over time the surface of the pot lightens in color from black to red or brown, but the core will frequently remain black due to short duration firing. This depends upon the length of time the pot is fired, and also how sandy or fine the clay is.

ck. Over time the surface of the pot lightens in color from black to red or brown, but the core will frequently remain black due to short duration firing. This depends upon the length of time the pot is fired, and also how sandy or fine the clay is.Some El Paso Brown shards have been fired sufficiently to burn out the carbon core entirely, but most contain black cores.

The El Paso Brown pottery was fired at a very low temperature of 1,100 to 1,500 degrees F (600 to 800 degrees C), and this firing may have taken less than one hour. These pots would hold water for a little while, but were fairly porous to liquids if stored for long periods.

Compare this to stoneware which was fired in kilns in Europe from the early 1400s to the 1600s. This pottery was fully fused and was virtually impervious to liquids. The firing of this stoneware typically t

.jpg) ook several days and then an equal amount of time or more to cool down before the potter could safely empty the kiln. The temperature needed to vitrify this clay into a very low porosity and re

ook several days and then an equal amount of time or more to cool down before the potter could safely empty the kiln. The temperature needed to vitrify this clay into a very low porosity and re.jpg) lative high strength true stoneware was 2,400 to 2,500 degrees F (1,300 - 1,400 degrees C). Note that this is a really high temperature; a little beyond cone 10 for people who use kilns.

lative high strength true stoneware was 2,400 to 2,500 degrees F (1,300 - 1,400 degrees C). Note that this is a really high temperature; a little beyond cone 10 for people who use kilns.While the pottery made by the Jornada Mogollon people may have been somewhat primitive when compared with the Romans or Greeks, I am certain that virtually all El Pasoans living today would not survive more than a few days at most if they were stranded out in the Chihuahuan desert surrounding El Paso.

-

The native peoples were very intelligent and hardy indeed.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-